Blackrock - A new breed of financial monster

- Details

- Category: Blackrock, Vanguard and Statestreet

- Created: Tuesday, 01 March 2022 22:58

- Written by John Moore - The Socialist Correspondent

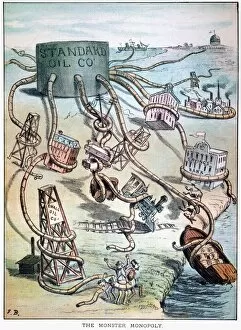

“By 2028 BlackRock Corporation and Vanguard are set to control $20 trillion of assets. That’s more than the combined GDP of India, Japan and Germany.” This is a degree of capital concentration that is historically unprecedented. Have you heard of BlackRock Corporation? Maybe not. Yet BlackRock is the biggest finance company in the world, with more than $8.2 trillion under its management (Yahoo Finance, 13/1/21).

“By 2028 BlackRock Corporation and Vanguard are set to control $20 trillion of assets. That’s more than the combined GDP of India, Japan and Germany.” This is a degree of capital concentration that is historically unprecedented. Have you heard of BlackRock Corporation? Maybe not. Yet BlackRock is the biggest finance company in the world, with more than $8.2 trillion under its management (Yahoo Finance, 13/1/21).

SHADOW BANKING

The financial crisis of 2008 threw up a new breed of capitalist monsters, according to Werner Rügemer (Strategic Culture, 23/4/21), including hedge funds, ‘locusts’ (private equity investors) and asset managers like BlackRock. BlackRock manages and invests money like a bank but without being restricted by banking regulations. The immense power of this ‘shadow bank’ is based on its control over a vast network of interests, giving it a hold over almost every sector of the economy. In the US, BlackRock is the controlling shareholder of all the major banks, big pharma, oil and tech giants, agribusiness, airlines, automotive companies, arms manufacturers and the media. It effectively has a controlling interest in Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, Tesla, Pfizer, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan. BlackRock’s reach extends to at least 30 other countries, including France, the UK, Switzerland and Germany. In Germany, it is the biggest stockholder on the DAX index, equivalent to the FTSE.

In Britain, BlackRock controls assets worth double the UK’s annual GDP, according to Nils Pratley (Guardian, 6/4/17). It has a stake in every FTSE company and is the biggest shareholder in over half. Its biggest stake by value is its £9 billion investment in HSBC. Other major shareholdings worth more than £5 billion are AstraZeneca (of which it owns 10%), British American Tobacco, GlaxoSmithKline, and Royal Dutch Shell.

BlackRock’s power is largely hidden. Heike Buchter, who has written about the company, titled the first chapter of her book: “The most powerful company no one's heard about.” Buchter says: “If you only look at the individual businesses BlackRock is involved in, you don't necessarily realize there's a problem. But add them all up – all the [company's] lines of business and advisory roles – and you end up looking at a massively complex structure, where you have to wonder: Wow, what kind of monster have they created here.” BlackRock’s method is to buy up around 5-10% of a company’s shares, which appears unthreatening – but that slice of ownership gives it enough lobbying power to control it, especially when it acts in concert with Vanguard and State Street, the third of the Big Three asset management companies.

Because BlackRock is not legally a bank, it can evade banking regulations, which were tightened after the 2008 crash. Its unregulated status enables it to deliver higher returns to investors than any bank. BlackRock uses shell companies in tax havens like the tiny US state of Delaware, the Cayman Islands and Luxembourg to avoid tax and scrutiny. Delaware, since the 1920s, has been home to the powerful pharmaceutical company DuPont (recently merged with Dow), of which BlackRock is a major shareholder. Throughout World War 2, DuPont provided technology to the Nazi war effort and made profits from IG Farben’s slave labour in Auschwitz. With Joe Biden as its Senator between 1973-2009 Delaware grew into the world’s biggest corporate financial haven.

Interestingly, BlackRock is willing to submit to Chinese regulations in order to acquire stakes in China’s leading companies and to obtain licenses for financial operations in China.

BLACKROCK'S GLOBAL POWER

Before the 2008 crash, Goldman Sachs played a similar role to BlackRock, on a smaller scale. Like Goldman Sachs, BlackRock is usually on both sides of mergers and acquisitions, which means it can shape them to its own benefit. But unlike Goldman Sachs it is not a bank and doesn’t invest directly, but rather manages other people’s investments. It’s a shadow bank. The term ‘shadow bank’ was coined by economist Paul McCulley in 2007. Laura E. Kodre of the IMF traces shadow banking back to the sale of individual US home mortgages which were bought up by finance companies and sold together in packages. This was how BlackRock’s CEO Laurence Fink made his money in the 1980s.

Shadow banks take out short-term loans from the money markets and lend them on to investors as long-term assets. In the lead-up to the 2008 crash, as Kodre explains, “investors became skittish about what those longer-term assets were really worth and many decided to withdraw their funds at once.” When these investors defaulted on their loans, the shadow banks could not, by law, borrow money from the US central bank, whereas commercial banks could. Shadow banks also didn’t have traditional bank depositors, with funds covered by insurance. This made them vulnerable. Because shadow banks were outside regulation and were not open to scrutiny, nobody knew the true value of their assets, and confidence in them crashed. Former US Treasury Secretary, Tim Geithner blamed a run on the shadow banks for triggering the 2008 crisis. But BlackRock managed to use the crash to its advantage – a case of one parasite feeding off another. In 2009, when credit was squeezed and many banks were failing, BlackRock saw an opportunity when Barclays Global Investment ran into trouble and needed to sell. It acquired Barclays Global Investment for $13.5 billion, using money from investors worldwide, in one swoop devouring the world’s biggest asset manager and becoming the leading player itself. “They were in a position to play offense while everyone else was scrambling,” says financial analyst Kyle Sanders.

The Covid-caused financial crisis represented an even bigger opportunity for BlackRock than the previous crash. The US central bank, the Fed, handed over to BlackRock the right to distribute the $2 trillion stimulus package agreed by Congress to prop up the US economy. All scrutiny of its role has been closed off by the suspension of the Freedom of Information Act for the Fed. As Kate Aronoff, writing in the New Republic, concludes: “BlackRock is having a very good pandemic.” Pepe Escobar goes further (Islam Times, 6/4/20): “Now, for all practical purposes, it [BlackRock] will be the operating system – the Chrome, Firefox, Safari – of the Fed/Treasury.”

Bloomberg calls BlackRock “The fourth branch of government”. During the 2008 crash, BlackRock CEO, Laurence Fink, a major donor to both Democrats and Republicans, offered the company’s risk analysis expertise to the US administration. Obama relied on BlackRock, just as Biden relies on it today. BlackRock executives play a key role in the current US government, providing the administration’s chief economist, deputy Treasury secretary and the chief economist for Vice-President Kamala Harris. BlackRock’s role ‘advising’ central banks is not limited to the US. It advises the European Central Bank, and its influence in Germany is exerted through former politicians such as Friedrich Merz, ex-chair of the CDU in the Bundestag, and bankers like Michael Rüdiger, who is on the board of Deutsche Börse. In the UK until early 2021, BlackRock was paying George Osborne a £650,000 salary to act on its behalf. On the global stage, Laurence Fink is now the acknowledged spokesman for the World Economic Forum (Davos). He is vocal on climate change, calling for a renewed green capitalism. Meanwhile, BlackRock controls the biggest fossil fuel and mining companies in the world, with $85bn (£62.1bn) invested in coal. A report by watchdog Majority Action found that BlackRock and Vanguard defeated 16 climate-related shareholder resolutions in 2019.

BlackRock represents a dangerous new stage in the monopolisation of finance capital, the high degree of which makes for tremendous instability. Crises are inherent in the irrational capitalist system and cannot be averted. The more monopolised the system, the more quickly a financial infection can lay the whole system to waste as we saw in 2008. Financial commentator Martin Wolf bemoans the fact that the “dynamic” capitalism he once knew has degenerated into a system of “unstable rentier capitalism” (Financial Times, 18/11/19). Nothing has changed since 2008. The parasitism has only deepened, and the monopoly power of BlackRock threatens the system as a whole.

Another financial crash is only a matter of time.

Source : https://www.thesocialistcorrespondent.org.uk/articles/blackrock-a-new-breed-of-financial-monster/